Sunday, November 29, 2009

Signs For The Times

I have a longtime fascination with old signs and am drawn to them as photographic subjects. Odd juxtapositions also interest me – in writing, in imagery, and in life in general.

This penchant of mine may be rooted in a scene I saw daily while growing up, the view from the front porch of my childhood home. Across the two-lane highway from our house was the neighbor’s barn. The east side of the barn was covered with two painted signs. At the top was a sign with a painted cross and scripture warning: “Christ is coming soon. Are you ready?” Below it a tobacco sign urged: “Chew Mail Pouch Tobacco. Treat yourself to the best.” Drivers traveling west of Route 22 often stopped to take a photograph. It took me years to understand that it wasn’t the bucolic scene, but rather the incongruity of the signs that attracted their interest.

The old farmer who owned it wasn’t getting paid for the advertising space, but instead got his barn painted by the tobacco company for free. I don’t know who sponsored the religious sign, but over the years the Mail Pouch advertisement faded while the scripture and cross were repainted again and again. The signs on that barn may have been the topic of more than one Sunday morning sermon among the local churches.

Billboards have changed over the decades, but they still try to sell the American dream to passersby. Trademarks and logos have become part of the landscape and language. Burma Shave signs and slogans may be relics of the past, but Coca-Cola thrives on youthful rejuvenation and digitized billboards.

I only recently connected my interest in signage to Walker Evans’ photographs, noticing Evans had a fondness for photographing advertisements and that Coca-Cola signs recur in his images. Evans used signs within his photographs to show the division of classes – the American dream beyond the reach of those who could barely feed their families in the dire economic times of the Great Depression. He juxtaposed advertisements for Hollywood movies and luxury travel with the poverty and struggle of people who had no hope of escape.

I cannot think of billboards and the American dream without remembering the image of the optometrist’s billboard in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Key scenes are played out under the spectacled eyes advertising the optometry services of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg. The Great Gatsby is about the American dream, about the pursuit of wealth, and about social strata. The reminiscent narrator, Nick Carraway, is an observer, an outsider, a distant cousin from the Midwest who is trying to make sense of the New York world and of the events that happened in the story he is relating.

It’s a timeless story, one of ruthless people living large on money that is inherited or made through get rich quick schemes. It has particular resonance today in light of Ponzi schemes and Bernie Madoff bilking his clients out of their life savings, or in simply watching our 401Ks tank along with the dream of retirement. No doubt the signs are always there for us. Unfortunately we can’t always see them until they are behind us and we’ve traveled far down the road.

News and Updates:

Thanks to writer Cynthia Newberry Martin for the shout out on her blog Catching Days about my posts on abandoned things. Cynthia has been a regular reader and frequent commenter at In This Light, and I’m grateful for her ongoing support and enthusiasm for what I’m doing here.

Photograph credits:

“Painted Signs, Grafton, West Virginia” copyright 2008 by Dory Adams

“Movie Theater on Saint Charles Street. Liberty Theater, New Orleans, Louisiana” by Walker Evans. FSA, Library of Congress, LC-USF342-T01-001285-A.

“Mixed Signs, Roanoke, Virginia” copyright 2008 by Dory Adams

Sunday, November 22, 2009

Follow the River: On The Road to Moundsville, West Virginia

On the final day of our October road trip, we spent the afternoon in Moundsville, West Virginia. The first stop was the West Virginia State Penitentiary. While waiting for our tour to begin, I looked at a display of old newspaper clippings about the filming of Fools’ Parade, which was based on Davis Grubb’s novel of the same title. The 1971 movie, filmed on location in Moundsville, starred Jimmy Stewart, George Kennedy, Anne Baxter, William Windom, and Kurt Russell, and it must’ve been a very big deal to have Hollywood come to Moundsville. The articles included photographs of the movie stars in town during the filming, but what really caught my attention was a paragraph near the end of one article: Before the excitement of the movie production, only three copies of Grubb’s book had been sold locally. After the filming, 3400 copies were sold in Moundsville.

The prison offers a haunted tour each year around Halloween, but we wanted to go on the regular tour. Reality was scary enough. In fact, I’m pretty convinced that if I were locked up in one of those 5’x7’ cells, as the inmates were with at least one and sometimes two cellmates, I’d be rioting at the first opportunity. If an inmate wasn’t an animal the day he was incarcerated, he most certainly was after a few hours on the inside. This penitentiary seemed far worse than Alcatraz (which I’ve also toured). Our guide told us that the cell block pictured above, temperatures could reach 120 degrees on the top tier in summer, and in winter the average temperature on the bottom tier was a damp 40 degrees. The penitentiary was finally closed in 1995, after the small cells and conditions were deemed cruel and inhuman punishment by the West Virginia Supreme Court. Evidently one woman on our tour did not agree with that decision since at nearly every stop on the tour she proclaimed “and that’s the way it should still be today.” I’m against the death penalty, but by the end of the 90-minute tour, which concludes in an area where the electric chair is on exhibit, she had nearly changed my mind. By that point I was hoping they’d let her sit in Old Sparky.

Davis Grubb was not a favorite son of Moundsville, and described himself as “the sore thumb on the hand of the town” in a conversation with Norman Julian (scroll down to the second essay by Julian, via the website of Meredith Sue Willis). Our prison tour guide stressed that the inmates Davis had based characters on were highly fictionalized and that the real convicts were the hardest of criminals. He was especially critical of Fools’ Parade, where ex-convict Mattie Appleyard is set up by the town’s banker, prison guard, and sheriff (Jimmy Stewart played the role of Mattie Appleyard in the film).

After leaving the penitentiary, we went looking for Davis Grubb’s childhood home. In the foreword to the Appalachian Echoes edition of Fools’ Parade (published by the University of Tennessee Press), fiction editor Thomas E. Douglass describes Davis as traumatized by the loss of the family home after his father had remortgaged it to obtain a business loan. The family was evicted just before Christmas in 1934 after the loan was defaulted. Douglass writes of Grubb’s childhood home: “It was an idyllic life, living in the large rambling two-story frame house at 318 Seventh Street, mere blocks away from the river and the train tracks that ran along its banks, not far from the Indian burial mounds, for which the town was named. The house was also near the West Virginia State Penitentiary and the Strand Theater, other places that would become firmly fixed in his imagination . . . . He carried a photo of the house with him throughout his life . . . . On his way to school, young Davis walked past the oldest structure in town, the Adena Indian burial mounds . . . and the West Virginia State Penitentiary, one of the oldest in the nation, built in 1866 like a gray granite castle. Walking by the prison’s twenty-four-foot-high wall, four-feet thick, Grubb did not fear those inside nor the possibility of their escape, but rather felt sorry for the inmates, who were cut off from life and separated from their families. Grubb once wrote ‘[I]n the innocence and confusion of my child’s brain, the great mound and the penitentiary were bound together in ambiguous and dreadful brotherhood. One was the burial place of the unknown dead; the other of the unknown living’ [in “The Valley of the Ohio,” 56].”

The Grave Creek burial mound is directly across the street from the penitentiary. As I mentioned in an earlier post, both can be seen from the nearby elementary school. Our itinerary following the penitentiary tour included a stop at the Grave Creek Mound Archaeological Complex. And, to end the day on a light note, we visited the Marx Toy Museum, where we indulged memories of our own childhood imaginations while looking at displays that included some of our own favorite toys, as well as a few we dreamed of but are still waiting to receive.

News and Updates:

Lee Maynard’s newest book The Pale Light of Sunset has just been published by the West Virginia University Press. Read a review by Cat Pleska at Meredith Sue Willis’ blog and listen to a podcast interview with Lee at WV Writers, Inc.

Photo Credits

Top photo: WV State Penitentiary Interior, copyright 2009 by Dory Adams

Middle photo: Cell Block, copyright 2009 by Dory Adams

Bottom photo: Cell Graffiti, copyright 2009 by Kevin Scanlon, used by permission

Sunday, November 15, 2009

Lens and Pen as Mirrors: Guest Post by Misko Kranjec

(Click on images for larger view)

[I’m honored to host a guest post this week by Slovenian photojournalist Misko Kranjec. I met Misko in the spring of 2007 when he traveled to the United States to give a presentation at the Center for Railroad Photography and Art’s annual conference. He spent several weeks touring the U.S. on that visit, including a few days photographing in Pittsburgh prior to traveling to the Chicago area for the conference. Misko is an award-winning photographer and the son of writer Misko Kranjec. ~ Dory]Lens and Pen as Mirrors

When Dory invited me to write a short reflection of how my father, a prominent Slovenian writer, and his writing influenced my photography, I thought it would be a piece of cake – a few sentences, blah, blah blah, and voila – done. This was not because I would undervalue Dory's blog and her endeavor in any way; I was just overestimating my capacity to analyze myself, and in English on top of that.

Actually, I never gave much thought about my own photographic aims – the concepts and inner meanings, or the mission of my work. I was just an observer of the world with the camera, recording what attracted my eyes and triggered my feelings. I didn't make a fuss of my efforts. For me, photography was always fun, and throughout the 30 years of my photojournalistic career, I always tried to keep it this way.

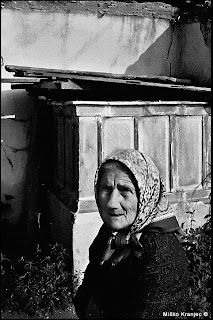

My father was a prominent writer in his time, kind of a Slovenian Faulkner, writing about Prekmurje – that northeastern region squeezed between Austria, Hungary, and the Mura River – and of the people living there. At the time of his birth in 1908, this region still belonged to the Hungarian part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, but after the First World War it was associated to the new born Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Totally rural and without any industry worth mention, this region was extremely poor. Half of it was either swamp or covered with thick forest, most of it belonging to the Hungarian Count Zichy family who had a castle in Beltinci and owned the biggest part of the arable land. What was left was far from being capable of sustaining the peasants living there, so the men either temporarily left their families to work as seasonal hired help in other parts of Yugoslavia or abroad, or whole families immigrated, mostly to the United States, Canada, or to the countries in South America.

After the WWII and with the birth of the Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia, the last of the Zichy Counts, the Countess Maria Zichy, fled to Austria. The land and the castle were confiscated and turned into a state farm. The swamps were mostly dried and turned into fields or grazing land and divided among the farmers. Significant progress came to this region and several factories were built, yet the region still remained predominantly rural, underdeveloped, and poor. What money came in was mostly from those working temporarily in Austria, Germany, and

France.

However poor they were, the people living in Prekmurje were extremely friendly and open, willing to invite even a stranger into their modest homes and share with him the last loaf of bread and the last bottle of home-grown wine. Those were the people and the land my father wrote about, and when I started with my photography back in the early 1970s, the scene there was pretty much the same as it had been decades earlier. While many new houses had been built, and cars and tractors started to emerge in ever greater numbers, there were still numerous clay-plastered wooden cottages with thatched roofs, carts and plows were still draw by cows, and the farmers, especially the women, still dressed as they did a century ago.

All this gave me a great opportunity to record on film at least a bit of what my father wrote about in his novels. True, the scene was changing rapidly and it took some careful framing to avoid the signs of modern times in order to re

cord it as it had appeared in the past. Perhaps I could even be accused of deliberately twisting the truth, but in this case it was not the truth or the present I was aiming for, but rather the past – the world of my father which gave him so much inspiration and so many stories and human destinies to write about.

cord it as it had appeared in the past. Perhaps I could even be accused of deliberately twisting the truth, but in this case it was not the truth or the present I was aiming for, but rather the past – the world of my father which gave him so much inspiration and so many stories and human destinies to write about.Disappointed with my first attempts to write about this for Dory’s blog, I decided to steal from my father by translating from the beginning of his book Youth in the Swamp, one of his last novels which is actually a biography of his childhood. So I started to translate this part of his book, and became too excited with my doing it to stop. Some of my father's work has been translated in several languages, but none in English. In front of me was my father’s book about his youth in this poor land, and on the very first inner page, before the title, written in his handwriting was inscribed: To my son Misko, as the mirror to the long gone days. January 15th, 1963. I was sixteen at that time, and little did I know that one day I’d be holding a mirror of my own – the camera.

As a kid, I was often in Prekmurje. During the summer holidays my father would take me with him whenever he would go there to write in the house that he, my mother, and his brother had built before World War II, which replaced the thatched-roof cottage where he was born. Back then, I didn't even like Prekmurje very much. We would stay there for two or three weeks, and these were very long and boring weeks for me. I was a city boy, and at home I had friends that I would play with the whole day long, every day in summer. But in Prekmurje, I had no other friend but the son of the school master. All the others were peasant kids, who spoke a dialect I could hardly understand. While my father was writing, I was left to my own devices which meant mainly reading books, playing with my toys, and feeling lonely and bored. In fact, I hated Prekmurje then.

Years later, during my leave from army service, I happened to visit Prekmurje for a day, and there I met a lovely girl who would inspire about a hundred love letters, and later sh

e became my wife. With that moment, my eyes viewed this land in a totally different light. We visited relatives there at several times a month, and her home became the base for my photographic explorations. Even though it was in the early 1970s, modern times had not yet really touched this remote land. The old people, the old cottages, and the old way of living – everything in fact that my father had written about in his books – was still very much present. I was just taking my first serious, formative steps into photography then, and my father's world suddenly became a great subject for my camera. It also became very, very close to my heart.

e became my wife. With that moment, my eyes viewed this land in a totally different light. We visited relatives there at several times a month, and her home became the base for my photographic explorations. Even though it was in the early 1970s, modern times had not yet really touched this remote land. The old people, the old cottages, and the old way of living – everything in fact that my father had written about in his books – was still very much present. I was just taking my first serious, formative steps into photography then, and my father's world suddenly became a great subject for my camera. It also became very, very close to my heart.I may have thought I hated this land as a kid, but actually I was soaking its spirit into my blood. The love for it and for its people had been hidden within me, but as I photographed, those feelings and affection surfaced. The people of my father's books were suddenly there, in blood and flesh, standing in front of me, speaking to me, inviting me into their homes, offering me their wine and food. Just as the people had come to life, so had the words my father put onto the page – all with new meaning.

Looking through the viewfinder, I felt them in my mind and they spoke to me and guided my eye while I was framing, and even then I did not yet realize that I was holding a mirror to those long gone days too. Yes, they were still there, as though frozen in time, not really the past yet – but it was fast thawing and running out.

Today, I am happy I had the chance to record the last remains of this world. In less than a decade the scene changed completely - the lovely old cottages were replaced with the modern houses, big John Deeres replaced the cows, and the old people died, one by one. In the mid-1980s there was almost nothing left of the old Prekmurje to photograph, and what remained was mostly weed-grown ruins.

I don't know whether it was an omen, destiny, or just coincidence that my father died in that same time. Unfortunately with his death also started the process of the oblivion of his work, more or less triggered by events which followed the secession of Slovenia from Yugoslavia in 1991. This was a time when the regime here changed to the right, to the conservative side, which considers my father as a "red" writer, writing foremost about the poor and deprived but good-at-heart people, the peasants from his Prekmurje, and because he openly favored socialism. Not a single book of his has been reprinted since his death, and I can openly say he was deliberately pushed into this state of oblivion.

I don't know whether it was an omen, destiny, or just coincidence that my father died in that same time. Unfortunately with his death also started the process of the oblivion of his work, more or less triggered by events which followed the secession of Slovenia from Yugoslavia in 1991. This was a time when the regime here changed to the right, to the conservative side, which considers my father as a "red" writer, writing foremost about the poor and deprived but good-at-heart people, the peasants from his Prekmurje, and because he openly favored socialism. Not a single book of his has been reprinted since his death, and I can openly say he was deliberately pushed into this state of oblivion.Well, actually not quite, as last year was the 100th anniversary of his birth and suddenly he was remembered again – for a brief moment. The Association of Slovenian Writers organized a literary evening, held in one small auditorium of the big cultural center in Ljubljana, where writers and poets from Prekmurje read their works in honor of my father. Five days before this event, one of them remembered that I had photographed Prekmurje extensively and thought it would be good to show my photos during the reading.

They asked if I would prepare a photo show. At first I refused, as this would mean scanning and retouching many photographs from negatives that I hadn’t held in my hands for at least 25 years. I calculated I would need between 300 and 400 images for a two hour event, to be shown on a screen during the reading. However, after more thought, I changed my mind. First, because of my father; I said to myself, I owe him this. And second, because of me; it had been a while since I’d had an exhibition of my photographs, and I told myself, it is always good to show people you are still around, important to defy oblivion.

[To see more of Misko's Prekmurje photographs, visit his online gallery.]

Photo Credits: All photographs copyright Misko Kranjec, used by permission.

Labels:

Misko Kranjec,

photographers,

photojournalism,

Prekmurje,

Slovenia,

writers

A Slight Delay in the Scheduled Guest Post

The publication of this week’s guest post will be delayed until Monday. Please check back tomorrow evening for a guest post by Slovenian photojournalist Misko Kranjec.

In the meantime, this gives me a chance to add a post about the recent Best Books of 2009 top ten list from Publisher’s Weekly. You’ve no doubt heard the outcry that not a single woman writer was named on the list. Kamy Wicoff, Founder and CEO of She Writes (of which I am a member), posted a wonderful editorial emphasizing her outrage at PW’s justification for coming up with a list that was not only exclusively male, but also 90% Caucasian.

There have been a flurry of posts at She Writes in response to Wicoff’s call to action, including one by writer Cathy Day about branding and book jackets as part of the literary gatekeeping.

In regard to the Publisher’s Weekly list, I can only shake my head in amazement that Jayne Anne Phillips’ Lark & Termite was not included. Phillips is the featured author in the winter 2009 issue of Appalachian Heritage, where you can read an

excellent profile of her by another West Virginia writer, Meredith Sue Willis.

In the meantime, this gives me a chance to add a post about the recent Best Books of 2009 top ten list from Publisher’s Weekly. You’ve no doubt heard the outcry that not a single woman writer was named on the list. Kamy Wicoff, Founder and CEO of She Writes (of which I am a member), posted a wonderful editorial emphasizing her outrage at PW’s justification for coming up with a list that was not only exclusively male, but also 90% Caucasian.

There have been a flurry of posts at She Writes in response to Wicoff’s call to action, including one by writer Cathy Day about branding and book jackets as part of the literary gatekeeping.

In regard to the Publisher’s Weekly list, I can only shake my head in amazement that Jayne Anne Phillips’ Lark & Termite was not included. Phillips is the featured author in the winter 2009 issue of Appalachian Heritage, where you can read an

excellent profile of her by another West Virginia writer, Meredith Sue Willis.

Sunday, November 8, 2009

Follow the River: First Stop Cincinnati -- Union Terminal, Roebling Suspension Bridge

Last month we took a road trip along the Ohio River – with no specific itinerary planned and no schedule to keep other than to follow the river, enjoy the fall scenery, and to stop when something caught our interest. We drove west to Cincinnati and then zigzagged our way back and forth across the Ohio River following it along secondary roads back to Pittsburgh, with a few short side trips along tributaries such as West Virginia’s Kanawha River. This was my first visit to Cincinnati, and two structures in particular there amazed me for their beauty and endurance: the Roebling Suspension Bridge and Cincinnati Union Terminal (now repurposed as “Cincinnati Museum Center at Union Terminal”).

We arrived near the end of the day, just in time to photograph the Cincinnati skyline and the Roebling Suspension Bridge in the evening sunlight from a vantage point across the river in Covington, Kentucky. The following morning we strolled across the bridge, which is well used by pedestrians. Completed in 1867, it was built by John Roebling who later designed the Brooklyn Bridge. Pittsburgh native David McCullough has written extensively about Roebling in his 1972 book The Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn Bridge and more recently in a Newsweek article arguing against new construction which would impede the view of the Brooklyn bridge.

I was struck by the sense of history which seemed to hover in the air around the late 19th century buildings on the Covington side of the river. While walking in the MainStrasse section, we passed the historical marker commemorating a famous slave escape just prior to the Civil War where slaves, including Margaret Garner who murdered her children rather than have them be recaptured and returned to slavery, fled the Covington area and crossed the frozen Ohio River to Cincinnati and the underground railroad. This real life event was the inspiration for Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved.

I was greatly impressed with Cincinnati Union Terminal, an Art Deco structure far more magnificent and dramatic seen firsthand than photographs convey. The 10-story art deco façade is fronted by a long driveway entrance and plaza with cascading fountain, with the fountain details repeating the shell shape of the terminal’s massive rotunda. The building now houses a complex combining the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History, The Cincinnati Historical Society and Library, a children’s museum, and an Omnimax theater – as well as an area which still functions as an Amtrak station for passenger service between Chicago and Washington, D.C. (passenger service had been halted completely in 1972, but was reinstated in 1991). The rotunda dome reaches a height of 180 feet above the open concourse, and the original interior details remain intact: signage, ticket windows, information kiosk, and two Winold Reiss mosaic murals.

The preservation and repurposing of Union Terminal is admirable. The city of Cincinnati purchased the terminal in 1975, and then along with the state of Ohio launched a successful restoration project in the mid-1980s with backing by voters, corporations, and foundations. Seeing the restoration first hand was inspiring, particularly in light of the potential the Buffalo Central Terminal holds if it could find similar support and backing. I’m becoming more and more convinced that one of our great disgraces as a comparatively young country is that we destroy our architectural history – not just our big city structures, but also those in smaller towns where suburban sprawl, chain stores and restaurants, strip malls, and Walmart Superstores have invaded to make them look exactly alike.

News and Updates

There are two upcoming local readings of note for Pittsburghers:

Stewart O’Nan will read at Joseph Beth Booksellers (East Carson Street, SouthSide Works) on November 12th at 7:00 PM. O’Nan’s newest novel is Songs for the Missing.

Chuck Kinder, Karl Hendricks, and Brendan Kerr will read at 8 PM on November 18th at The New Yinzer season finale at New Formations (4919 Penn Avenue).

Photo credits:

Roebling Suspension Bridge, Cincinnati Museum Center at Union Terminal © 2009 by Dory Adams

Sunday, November 1, 2009

The Picture that Inspired 80,000 Words: Christina Baker Kline's BIRD IN HAND

[It’s my pleasure to host a guest post this week by novelist Christina Baker Kline]

The newspaper clipping is in tatters. Folded, yellowed, curling at the edges and mended in places with clear tape, it was tacked to the bulletin board in my office for eight years – except for the times I brought it with me to writers’ colonies or on family vacations (under the delusion that I might actually get work done on a beach).

The newspaper clipping is in tatters. Folded, yellowed, curling at the edges and mended in places with clear tape, it was tacked to the bulletin board in my office for eight years – except for the times I brought it with me to writers’ colonies or on family vacations (under the delusion that I might actually get work done on a beach).More than a decade ago, leafing through The New York Times, I came across this image as I was beginning to work on a new novel. I assume that it was part of an advertisement, but I cut it out carefully around the edges, so I don’t know for sure. I don’t even know when it appeared in the paper, though from what I’ve deduced from articles on the back side it seems to have been some time in the spring of 1998. (An ad for a wine store says “Prices effective through April 30, 1998. © 1998.”)

The image floored me. I had begun writing about a young couple, Ben and Claire, both expatriates living in England, who befriend another American named Charlie … who falls in love with Claire. Who may or may not be falling in love with him. This picture in the newspaper, it seemed to me, perfectly encapsulated the complexity of my characters’ situation.

For many reasons, the story this photo tells is intriguing. A couple on a park bench sits close together, facing away from the viewer. The man has his arm around the woman’s back, his hand resting protectively on her shoulder. The woman’s arm is around his shoulder, as well … except that it isn’t. It extends along and behind the bench, and her open palm rests on the hand of a man on the other side, who kisses it tenderly. (A two-sided park bench? I don’t think I’ve ever seen one in real life.)

All the markers of romantic Paris – the French restaurant awning, the folded newspaper (Le Monde), the European car in the background and baroquely detailed (if blurry) streetlight in the foreground, a smattering of fat pigeons, even the man’s black turtleneck and the woman’s plaid skirt and sensible heels – contribute to the illicit thrill of this image.

Does the man on the other side of the bench have any idea that his girlfriend/wife is being unfaithful? Did she and the man kissing her hand plan to meet at this place, or was it happenstance? For that matter, do they know each other, or is this a spontaneous moment of anonymous passion? Did the photographer happen on this scene, or was he, perhaps, hired by the man with his back to us on the bench?

The image is shocking in its seeming casualness, in the brazen, in-broad-daylight transgression taking place before our eyes. I was fascinated by the contradictions: the woman so clearly part of a couple, yet making herself available to the man behind her, her demure pose contrasting with her open, searching palm. The man’s body language, too, is contradictory; he sits casually reading the paper, one leg crossed over the other, but his eyes are closed in passion as he kisses the woman’s palm.

Instinctively I knew that this image would help me access the core motivations of my characters, who act in comparably indiscreet and scandalous ways. Claire loves her husband, but she feels something entirely different for Charlie – a passion she’s never felt. Charlie respects Ben, but is blinded by his love for Claire. And when Claire’s best friend from childhood, Alison, comes to visit and ends up engaged to Charlie, things spin even further out of control.

This novel, now in bookstores, is called Bird in Hand. When I sent the final manuscript to my publisher about six months ago I took the tattered newspaper clipping down and put it in a cardboard box, along with my handwritten first draft of the novel. Now my bulletin board is covered with postcards from the New York tenement museum depicting the interior of an immigrant Irish family's cramped apartment, a black and white photograph of a young couple at Coney Island in the 1920s, a map of the village of Kinvara, Ireland, and othe

r inspiration for my new novel-in-progress.

r inspiration for my new novel-in-progress.Christina Baker Kline is the author of four novels, including, most recently, Bird in Hand and The Way Life Should Be. She is Writer-in-Residence at Fordham University and lives outside of New York City. Her website is www.christinabakerkline.com and her blog, A Writing Year: Conversations about the Creative Process, is http://christinabakerkline.wordpress.com.

Labels:

authors,

Bird In Hand,

Christina Baker Kline,

writing

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)